How can you support someone if you don’t fully understand their experiences, culture and community? How can you help them make the unfamiliar familiar? The short answer is: you can’t.

The issue of effectively mentoring African students surfaced as part of UBC’s work supported by the Mastercard Foundation Scholars Program—and from that, “Identities in Transition—From Africa to North America & Europe: Becoming Students,” a joint research project with Scotland’s University of Edinburgh funded by the Mastercard Foundation that wrapped in November 2022.

Interviews and data analysis on the project unfolded in parallel at both universities. With the Scholars as researchers, the participatory investigation focused on the intricacies of students transitioning from the African continent to study in Canada and Scotland, including the African experience, the role of mentorship, issues of race, and what it means to be Black in North American and European academia. It’s an area greatly lacking research, said Cynthia Nicol, project leader and UBC Faculty of Education Curriculum & Pedagogy Professor.

Students took pictures and wrote about their personal experiences related to home, community and transition to create a “photo-voice booklet” as a way to spark conversation and inspiration. One common theme was “making the unfamiliar familiar,” most successfully through family and food. Meetings took place mostly over Zoom, with the Edinburgh team led by Dr. Christina Sachpasidi. The UBC researchers visited Edinburgh last July for a week to collaborate on resource materials.

Faculty, staff and co-researchers from UBC and University of Edinburgh at a brainstorming session in Edinburgh, Scotland in July 2022 (photo: Marian Orhierhor)

The result—all uploaded to a website—is a “toolkit” for intercultural mentors of students from African countries, the booklet, 12 study cases and a podcast series, likely complete by spring 2023. The researchers are also presenting the findings at international conferences.

“This project underscored for me the huge courage it takes to leave your home and family, to travel so far away and be away for years while grappling with high expectations from your community back home; the risk it takes; and the strength to be able to create community around you,” Nicol said.

We spoke with three Identities in Transition researchers: recent UBC grad students Marian Orhierhor, Abigail Okyere and Andrews Nartey. Orhierhor is from Nigeria; Okyere and Nartey both hail from Ghana. The group also included Atang Koboti, Judith Nuhu, Anne Joseph and Kimani Karangu.

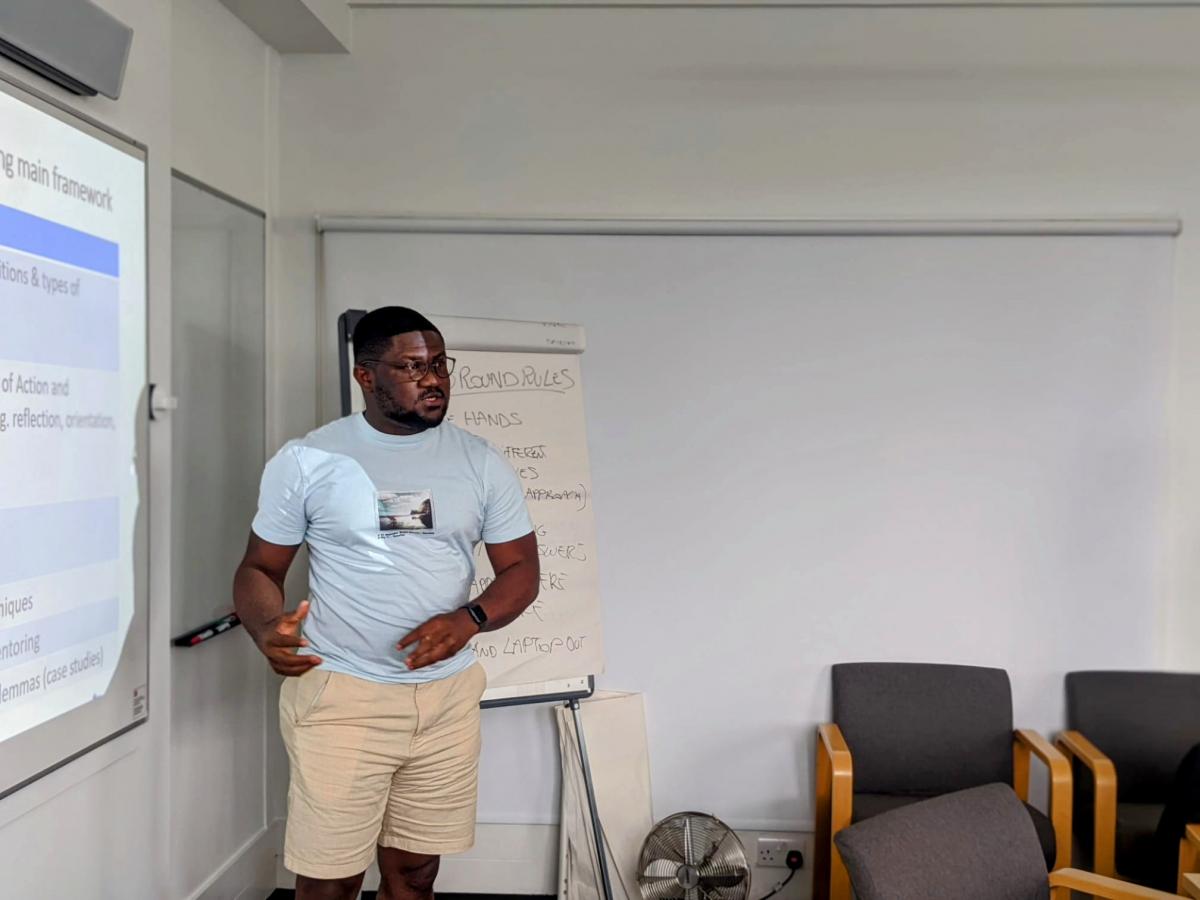

Andrews Nartey speaking at the UBC-University of Edinburgh collaborative session in Scotland in July 2022 (photo: Abby Okyere)

What’s the goal of this project?

Abigail Okyere: We wanted to hone in on the African perspective and see how students transition here. The experiences of international students are all different, and we really didn’t have any research or know-how on how African students are integrated into North American and European systems. There are so many changes—from cultural and personal to academic and social. As Africans, our cultures and experiences are unique; yet we’re all facing the same issues. We asked, how do we come up with some kind of guidelines for other African students making the journey? How do we help faculty and counselors here to help Africans integrate not just into the academic ecosystem, but social culture? One of the most important aspects within this goal was telling the African story by Africans. Usually, that is done by people who are not Africans.

Why is it important?

Andrews Nartey: So we can help future students who come here to study or pursue international work opportunities. The aim was to develop a robust “toolkit” based on experiences we shared—our stories of transitioning from Africa to Canada and the UK—so future students can have a template with strategies and resources; so they won’t be shocked if they run into any challenges. They will know this is what other students did to survive or thrive, and, we hope, this can ease the transition.

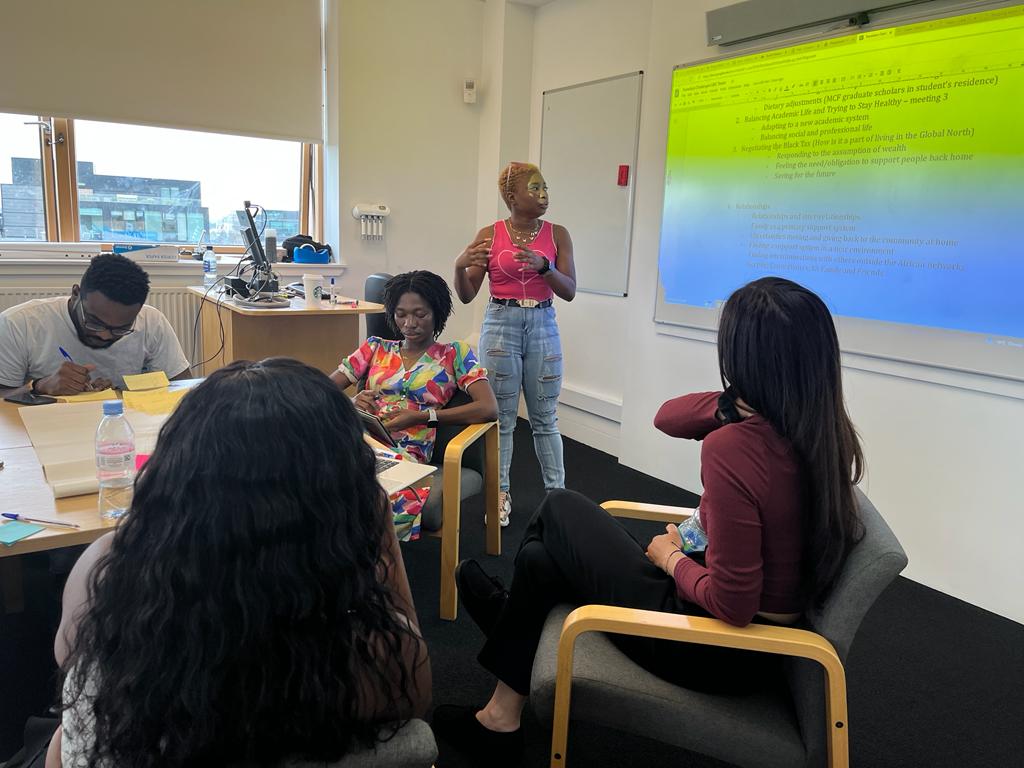

Abigail Okyere shares her ideas at the University of Edinburgh in July 2022 (photo: Marian Orhierhor)

What did you learn?

Marian Orhierhor: That it’s one thing to think others are going through the same thing, but actually hearing it is another. When we showed our photos and talked about them, that spurred conversations and highlighted shared experiences. When you realize this is not unique to you, it increases the sense of community. You process the fact that most of us had to go through similar challenges and we’re fine in the end.

Abigail Okyere: For me, it was coming to the realization that identities are fluid. You don’t necessarily see what is not there. For example, no one would refer to me as Black or a minority in Africa, but now people refer to me as Black. Some things you never thought of before—such as appearance—suddenly start to define you. It makes you ask yourself, how do you assimilate into another culture that is not your culture? That keeps shifting as we are learning about ourselves.

What are some of the common issues that surfaced?

Andrews Nartey: Home and food. African food is definitely different from North American or Mediterranean food. Getting the kind of food we want is a struggle, so most of us have had to resort to cooking at home. But that can also get tricky in terms of finding the ingredients. It’s hard to feel at home when you’re not eating what you want to eat. For me, I’m a foodie, so that was difficult for me.

Abigail Okyere: Community—having a sense of belonging: that one resonated with all Africans. In Africa, we have the concept of “village”; that it takes a village to raise a kid. We grow up with big families and can walk into anyone’s house and eat. Parents don’t have to worry about you so much because of the whole concept of community. One part of coming here to study is leaving your community behind, and you need that sense of belonging again. North American culture doesn’t really have that sense of community. So how do you integrate yourself into it? And even if you find it, you are not so sure that you can fully trust that new community, and you might stand out as the only Black person. So how do you build that sense of belonging?

Marian Orhierhor: The language sensitivity. For most of us, we are used to British English where we come from. Coming to North America, there are differences in dialect and intonation. It can be hard to understand accents and what people are saying. There’s also a new context: the meaning behind the words.

Abigail Okyere: Yes. We are very direct and used to speaking facts as-is. In Ghana, you can exchange words aggressively, and the next minute, you’re going for beers. It’s a challenge understanding the Canadian niceness, and how to sandwich facts in language that doesn’t offend unintentionally.

Andrews Nartey: Another piece of the transition story is people here not recognizing our qualifications earned back in our home countries. Many of us feel we have the skills and capacities for different professional jobs, but the mere fact that we are Black and Africans poses a great challenge to navigating the job market due to the wrong notion or misconception that Africans aren’t as excellent. That creates a lot of roadblocks for students when searching for work. We have the competence, but somebody else gets the job because that person doesn’t have an accent. That can be very frustrating.

Marian Orhierhor says the opportunity to exchange ideas in person proved extremely valuable. Marian at the University of Edinburgh in July 2022 (photo: Marian Orhierhor)

What’s the significance of researcher-as-participant?

Andrews Nartey: If participants are not researchers, there are some nuances that cannot be teased out. You end up with a story that is half-baked or lacking important elements. In our project, the research for Africans was undertaken by Africans, so we were able to bring our true authentic selves to meetings—and this can increase the utility of the research findings. As participants-cum-researchers, we were involved in various phases of the project: from literature review, data collection, data analysis and reporting, which results in a wholesome synthesis and interpretation of the findings.

What work still needs to be done in this area?

Marian Orhierhor: Important for me is how institutions will implement some of the solutions we have proposed. Often you see results shelved. But so much good has come from this project. I want to see our work utilized not just by UBC, but other universities and institutions, and adopted by faculty and staff. We need to incorporate more African perspectives in what we are doing.

Andrews Nartey: We hope that this research will provide a framework and serve as a platform to motivate a flurry of related research projects. Collectively, sufficient evidence can be generated to inform policy change that can benefit Africans and other immigrants. Also, I don’t see equity, diversity and inclusion actualized. It’s not supposed to be just a concept touted in the industry space; we want to see institutions practicing it.

Abigail Okyere: Gradually, we are getting to a point where, not just for Africa, but for every continent, we let those people drive the narrative. When you get perspective from folks who have experience on the ground, that elevates the research to another level. More and more, we are moving to a place where the narrative is driven by the people who are part of the topic.

Andrews Nartey at the collaborative session in Edinburgh, July 2022. Andrews wants to see the research results inform policy (photo: Marian Orhierhor)

Any surprises?

Andrews Nartey: I didn’t expect this project would take me to Scotland. To go to the UK to further engage on this project was a huge pleasant surprise! I was also surprised people were vulnerable and shared their stories without worrying about how others would perceive them—some were so sensitive and personal. I think in the end, we all felt empowered.

Abigail Okyere: The instances of microaggression participants shared, even coming from faculty—it was shocking. I see UBC as very diverse, with a lot of international students here, and Vancouver as culturally diverse. You settle in and you think it’s rare for some of these things to come up. But that’s not the case. And this drives home the point that a lot more work needs to be done to amplify equity, diversity and inclusion.

That said, our project director (Cynthia Nicol) leaned in to listen and was empathetic. Even the fact that UBC wanted to do this project, and is investing in it, is very heartwarming. That shows UBC is putting itself in a place where they want to learn and be inclusive; that they are willing to understand international students. The wealth of knowledge and experience we as Africans bring is enormous. We know there is work to be done.

On a lighter note: The other big surprise revealed was that when Black people here see each other, for example on the bus, they nod to each other. You don’t see so many Black people, so when you see them, you know they are resilient to have made the transition. You don’t know them, but you feel supported by that whole community. They give you a reassuring nod which means, I see you, too. That was a surprise, and a good one.

Marian Orhierhor gives a presentation to UBC and University of Edinburgh researchers during one of the Edinburgh sessions (photo: Marian Orhierhor, July 2022)

Find out more about the Identities in Transition project.

Learn about the Mastercard Foundation Scholars Program Research Project.

The Mastercard Foundation Scholars Program (MCFSP), envisions a transformative network of young people and institutions driving inclusive and equitable socio-economic change in Africa. Since launching in 2012, the Program has supported nearly 40,000 young people in Africa to pursue secondary or tertiary education. UBC has hosted 173 Mastercard Foundation scholars over nine years, with 23 graduate students and undergrads currently on campus. Program Director of Global Campus Initiatives Shanda Williams heads the MCFSP initiative at UBC, taking the reins from Jolanta Lekich as the new program director.