“The ocean is who we are,” says 19-year-old Lolobeyong Benito of the Northern Mariana Islands. “Without the ocean, why are we called Pacific Islanders? It is who we are.”

These seafaring people from Western Pacific Ocean islands in Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Federated States of Micronesia (Polowat Atoll) want the rest of us to know that while world superpower businesses and city-based peoples continue polluting, the people who live across Oceania are the ones feeling the acute effects of climate change.

Colonial international laws, and shipping and border restrictions on use of ancient ocean routes and current-ways, have nearly snuffed out intercultural exchange, trade and crucial interpersonal connection between the isolated island communities that need navigation by sea between each other to survive—as well as monitor and protect the ocean itself. The Indigenous peoples of Oceania want those policies to change. They want the world to know they have solutions to the climate emergency to offer and important wisdom to share. They want to start rebuilding a network of ocean caretakers all across the planet to safeguard eco-diversity, millennia-old traditions and their maritime cultural heritage.

A group of seven Pacific Island knowledge keepers accompanied by two supporters arrived at UBC on Vancouver’s shores Jan. 30. With delight they witnessed snowfall for the first time ever. Some in the group had travelled for weeks from their remote islands to meet with Musqueam community members and leaders, UBC researchers and students, and representatives from the BC Consular Corps, and to attend the global IMPAC5 conference on climate change and oceans. The visit was four years in the making—the outcome of a serendipitous meeting between two men one day back in 2019 on ṮEḴTEḴSEN (BC’s Saturna Island). This is the story.

Meet the ancestral voyaging leaders

How it all started

UBC Political Science Professor Dr. Yves Tiberghien first met Luke O’Grady Vaikawi on BC’s ṮEḴTEḴSEN (Saturna Island) in 2019. Vaikawi had travelled far to the U.S. and then Saturna to tell about the revival of his community’s canoe society heritage and recovery of ancient traditions back on Taumako Island, a remote community of 450 souls with no roads, phones or electricity in the Solomon Islands of the Western South Pacific. After a conversation about life in Taumako, the building of ancestral canoes, and the hopes of Luke and his community, Vaikawi held Dr. Tiberghien's hand, looked him in the eye and explained that his people needed to be heard. “Luke is a truly impressive human being: he has great energy and reflects deep truth and knowledge, recalls Dr. Tiberghien. “I always remembered him and missed him after that. It was a truly powerful encounter.”

That it was—because from that moment on, Dr. Tiberghien began collaborating with Vaikawi, Executive Director of Taumako’s Holau Vaka Taumako Association, on the idea of bringing Vaikawi and fellow Pacific Island knowledge keepers from distinctive islands in the region to UBC for a multidisciplinary dialogue on “different ways of knowing”—and to the global ocean protection congress IMPAC5 Vancouver so that their voices could be heard on the world stage. Dr. Tiberghien credits Marianne “Mimi” Kaveia George, who has devoted her life to supporting the cultural revival efforts led by Taumako people and others, as the critical link with the knowledge keepers and an essential partner in the collective effort.

Back row, left to right: Lolobeyong Benito, his dad Mario Benito, Daniella Weber, Sanakoli John, Kyle McDonald (a volunteer for the Vaka Taumako Project), Dr. Yves Tiberghien, Luke O’Grady Vaikawi; middle row, left to right: Modakula Kunuyobu, Setareki Ledua, Dr. Rashid Sumaila, Delsie Betty Bosi; front row, from left to right: UBC-Sciences Po undergraduate Lou Gindt, UBC Political Science master's student Sasha Lee and Mimi George at the Vancouver Convention Centre for the IMPAC5 conference (photo: Daniella Weber)

Adds Vaikawi: “To have people from these small islands coming to Vancouver… Yves had that vision."

There are few remaining people who retain the traditional knowledge of seagoing, especially on many isolated islands, Dr. Tiberghien learned from Vaikawi.

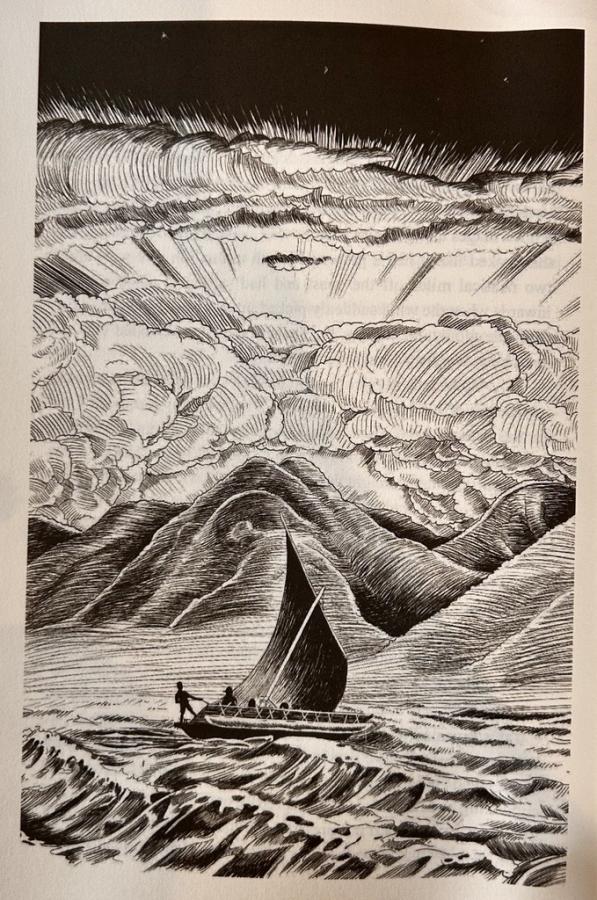

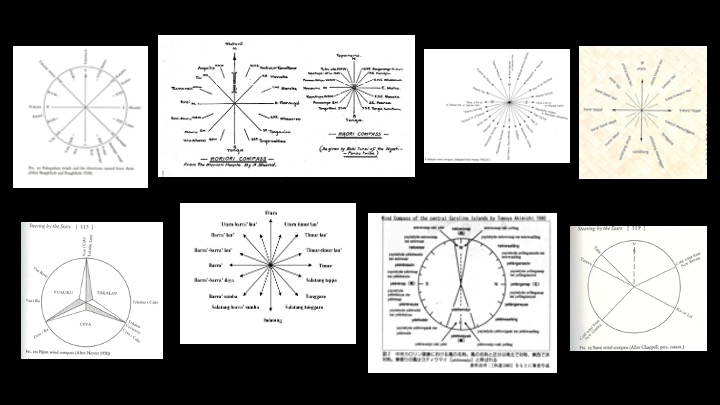

“Yet they have an extraordinary story of know-how of ocean navigation and migration over the centuries, which enabled people with very simple tools to achieve mastery of ocean—and understanding—unrivaled in human history,” Dr. Tiberghien says. “They managed to sail the whole Pacific Ocean: one-third of the entire world. Now we know they did it with wood canoes: navigating with stars, current flow, seaweed, fish, fish flow. They were also deeply connected to each other, the ecosystem, ocean, climate and animals.”

Though it might have seemed like a stretch at first, soon Dr. Tiberghien with his infectious positivity and genuine passion had roped in many others, including oceans expert Dr. Rashid Sumaila, University Killam Professor, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries; Canada Research Chair, Tier I, Interdisciplinary Ocean and Fisheries Economics. “Every time I saw Yves, he’d bring it up,” says Dr. Sumaila with a chuckle. “It wasn’t going to not happen.”

Says Dr. Tiberghien: “Rashid’s work is amazing and he is such a great friend. He knows what is important and the importance of interdisciplinary cooperation. This event could not have happened without Rashid, as well as the support of William Cheung [Director of the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries].”

Dr. Sheryl Lightfoot offered vital guidance early on. Dr. Tiberghien also approached the UBC Office of the Vice-Provost International, collaborating with former Vice-Provost, International Dr. Murali Chandrashekaran, and Office of the Vice-Provost International (OVPI) Managing Director Cheryl Dumaresq. Along with Dr. Rumee Ahmed, Vice-Provost, International pro tem, their support for the global initiative generated matching funds from the OVPI and IMPAC5 leadership to bring the guests to Vancouver and cover their stay. Daniella Weber, OVPI Associate Director, Strategic Initiatives, handled logistical support and coordination between the academic units.

Soon many others joined the effort, including:

- Dr. Andrea Reid, Assistant Professor, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries; Principal Investigator, Centre for Indigenous Fisheries

- Dr. Bernard C. Perley, Director, Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies, Associate Professor

- Dr. Alice Te Punga Somerville (Māori – Te Āti Awa, Taranaki), Professor, Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies and Department of English Language and Literatures, Faculty of Arts

- Dr. Susan Rowley, Director, Museum of Anthropology; Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology; Co-Academic Coordinator for Musqueam 101

- Dr. Carol Mayer, Curator, Pacific & World Ceramics at UBC's Museum of Anthropology

- Dr. William Cheung, Director of the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries

That four-year journey came to fruition Feb. 2: when seven UBC-and-partner-sponsored Pacific Island knowledge keepers hailing from remote Western Pacific Ocean islands and two supporters gathered at the Vancouver campus’ Liu Institute–xʷθəθiqətəm (Place of Many Trees) in a public event to share their extensive knowledge of ocean navigation and exchange perspectives in a discussion on climate change and biodiversity.

The aruduous trip marked the first time many had left their rural communities. Joining Vaikawi were: Delsie Betty Bosi, also from Taumako Island; Fji’s Setareki Ledua; Sanakoli John and Modakula Kunuyobu of Papua New Guinea; Mario Jacob Benito from Micronesia and his son Lolobeyong Benito from the Northern Mariana Islands; and, by request from Indigenous elders, Mimi George and Heu`ionalani Wyeth from Hawai`i.

The dialogue marks UBC’s renewed effort to rethink what knowledge means, Dr. Tiberghien says. “Knowledge cannot be restricted to scientific categories and approaches, although they are an important component. We believe that ancestral Indigenous knowledge, practices and arts have so much to teach us about our planet, our ecosystem, and the connections between humans and the natural environment,” he says. “This is a chance to listen and celebrate this extraordinary source of knowledge accumulated over thousands of years and ignored during colonial times. We have gathered to learn from the sea-voyaging people of the Western Pacific, whose ancestors achieved some of the greatest navigation feats in human history.”

The visit

A group of seven Pacific Indigenous knowledge keepers travelled to Vancouver in the chill of January from vastly diverse regions of the Western Pacific—perhaps the most “rare and significant” aspect of the visit, said Dr. Alice Te Punga Somerville (Māori – Te Āti Awa, Taranaki), Professor, Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies & Department of English Language and Literatures, Faculty of Arts.

Geographically far from each other, each island’s language and culture are very different. In fact, some 1,200 different languages are spoken in the region, notes Dr. Te Punga Somerville. Each strives in their own way to mobilize ancient knowledge by making deep-sea voyages on the ancestral sea roads and re-establishing inter-island networks that protect the oceanic world. They came with two allies from Pacific Traditions Society of Hawai'i to make people aware of their knowledge of the ocean, biodiversity and climate change issues.

The group made presentations and joined events at UBC and IMPAC5, a global ocean protection congress with a focus on Indigenous leadership in conservation. In fact, it was an extraordinary gathering, said Maritime cultural anthropologist and organizer Marianne “Mimi” Kaveia George: “The kind of knowledge embodied here is extremely exceptional and desperately needed," she said.

The group presented at a Feb. 2 public event at UBC Vancouver to a large and receptive audience (photo: Justin Man)

The overall aim, said the trip initiator UBC Prof. Yves Tiberghien, was to “bring together different ways of knowing across disciplines and cultures, through dialogues between the UBC and Musqueam communities and the sea-voyaging people of the Western Pacific to enrich our understanding of the complex inter-relationships of ocean phenomena and what must be done to protect and live with the ocean for our own future survival.”

“The ocean has received less attention than climate change or land biodiversity,” he added, “but the future of the ocean is essential to the planet’s future and human life.”

Said Centre for Indigenous Fisheries scientist Dr. Andrea Reid: “Climate change poses a profound threat for Indigenous Peoples and lifeways around the world. Just like Indigenous Peoples on this coastline, these Pacific sea voyagers hold critical knowledge of the ocean and navigating amidst uncertainty. This is the kind of knowledge, and knowledge keepers, we need to hold up in the highest regard in our institutes of higher learning, especially at this time of social-ecological crisis.”

It's only logical to pay more attention to the Pacific here in BC, noted Dr. Te Punga Somerville, because of UBC’s West Coast location: “There are a lot of Pacific academics appointed across different Canadian institutions, and it feels like there is a tidal move of people in this part of Canada asking: What does it mean to be not just on the West Coast of a continent, but the East Coast of an ocean?"

Dr. Tiberghien concurred. The Political Science professor persevered for four years to bring the distinguished Pacific guests to UBC. And he—as with many involved in the initiative—hopes the encounter will spark connections leading to joint knowledge and a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship.

Several UBC groups, alongside organizers George and Heu`ionalani “Meph” Wyeth, coordinated the Vancouver visit—with Musqueam community members, UBC scientists and students, and government and consular representatives—merging ocean science, geoscience, plant science and zoology, as well as cultural history and narratives, music, anthropology, archeology and navigation, to name a few.

It was an unusual initiative involving multiple units across the university, including UBC faculty, staff and students from the Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies, the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, the Department of Political Science and the Museum of Anthropology.

Collaborating on the UBC activities with Dr. Tiberghien were professors Dr. Te Punga Somerville, Dr. Reid, Dr. Rashid Sumaila, Dr. William Cheung, Dr. Bernard C. Perley, Dr. Susan Rowley and Dr. Henry Yu. The UBC Office of the Vice-Provost International housed the group at St. John’s College on campus, coordinated logistics, and financed trip costs with matching funds from Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Hailing from a wide range of islands in the region, some without electricity or telephones, the visitors travelled several weeks on canoes, boats, in planes and cars to finally arrive in Vancouver. Organizer George called the logistics very very complicated. “Visas were invented that never existed before,” she joked, noting assistance from high-ranking leaders in Ottawa to make it all happen.

The UBC program began Jan. 31 with a welcome lunch at St. John’s College. Honouring the guests from afar, the Musqueam Elders Centre hosted a dinner and dialogue on Feb. 1 as part of the Musqueam 101 speaker series. Other private UBC events included an Indigenous-focused campus tour and stops at The Office of Indigenous Strategic Initiatives and First Nations Longhouse; a private tour of the Museum of Anthropology collections; and lunch at Haida House hosted by the Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies. At Haida House, hosts and guests exchanged gifts.

The public joined a packed Feb. 2 dialogue and reception at UBC Vancouver’s Liu Institute for Global Issues–xʷθəθiqətəm (Place of Many Trees), which opened with a symbolic traditional blowing of the conch shell. The Pacific guests discussed “how ancestral voyaging mobilizes knowledge of biodiversity and climate change,” showing various film clips and photos in a range of presentations on the history and meaning of ocean-going navigation in their respective homes. [Watch the recorded event on YouTube.]

Dr. Bernard C. Perley, Director of UBC’s Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies, shared remarks on behalf of the university. He presented the guests with Haida blankets to keep the them warm during their stay and to "remember the friendships made here." The blankets feature a design by Haida artist Bill Reid, widely recognized as having revived the great tradition of Haida art. Created in 1976 for the Canadian Museum of History, the "Children of the Raven" motif celebrates the creation of humankind by Raven.

UBC student volunteers from multiple departments helped organize the event, setting up and decorating the space, designing the promotional materials and sharing on social media, arranging the food and receiving guests.

At the IMPAC5 conference—co-hosted by the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh along with governments and other partners—Feb. 3 to 9, the group presented as a panel to a standing-room only audience, many with tears in their eyes who stayed long after the event concluded to continue the conversation. They shared observations on what’s happening with climate change and the ocean, and what should be done from a holistic perspective, as well as their hopes to recover access to critical traditional ocean routes.

UBC Vancouver St. John's College hosted the Jan. 31 welcome event. Director Dr. Henry Yu greeted the esteemed Pacific Island guests in the dining hall (photo: Daniella Weber)

On the last day at the Vancouver campus, the travellers gathered with their luggage in the St. John’s College dining hall under the roof of 1,000 origami birds for a final lunch together with the organizers, and to prepare for the next leg of their journey. With tears on both sides, Dr. Tiberghien and Taumako Island’s Luke O’Grady Vaikawi embraced a long bear-hug farewell. It’s certain neither will forget any time soon the chance meeting four years ago on BC’s Saturna Island (ṮEḴTEḴSEN) that set the whole thing in motion…

Read the article about the visit in the UBC student-run newspaper, The Ubyssey.

The ask

A group of Western Pacific Island sea voyagers travelled across the world to meet other Indigenous knowledge-keepers, share their extensive experience & rally for policy change—this is their ask

1. Share traditional Indigenous knowledge for a better world

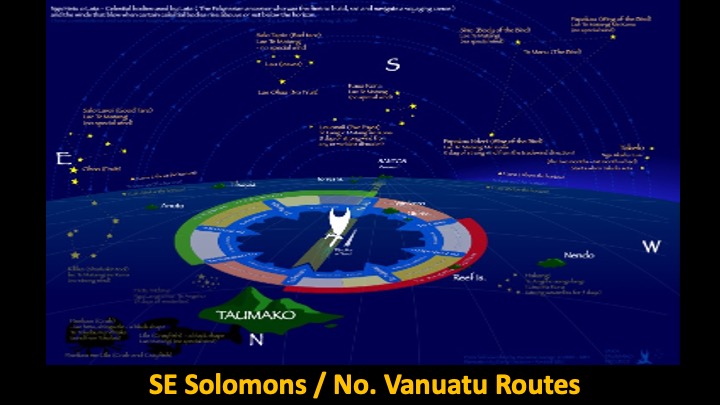

Traditional practices naturally promote the protection of the marine landscape and geography, the islanders maintain. On their remote islands, each clan has its own vessel—names include vaka, Drua, proa, wa, sailu, va’a and pahi. "Our whole community convenes to build a traditional outrigger canoe," explains Mario Benito of the Federated States of Micronesia. Together the men fell one carefully selected tree, he says. They use charcoal to draw carving lines. With adzes and using their own bodies to make measurements, they form the vessel piece by piece, notes Mario’s son Lolobeyong Benito. The process takes many months or more than a year, and one mistake with a razor-sharp adze can mean starting over entirely. The men coat the wood to seal it in sap extracted from a tree and mixed with charcoal, applied with a coconut husk. Rope-making from pandanus fibre is an essential task. There is always a blessing before embarking on a sea journey. Mario Benito’s 500 Sails nonprofit—named after the 500 sails that the first Europeans saw when they arrived at Saipan in 1742... and soon vanished. 500 Sails taps ancient knowledge to teach others as they craft modern canoes. “Our goal is to bring back maritime traditions once lost,” he says.

Adds Papua New Guinea’s Sanakoli John: “Our principles are: No. 1 respect, and 2 and 3, sharing and loving. We only take what we need, and we make everything ourselves.”

Sanakoli John and two fellow islanders from Papua New Guinea reached their starting point in Milne Bay on Oct. 20, 2017, completing a record circumnavigation of New Guinea Island, the world’s second-largest, on a traditional hand-hewn sailau (outrigger canoe). “We were very proud, but also looking forward to a good rest,” said the ever-humble captain. A documentary film on the odyssey, “Sailau,” debuts this year (photos: Thor F. Jensen)

During the trip around New Guinea Island in 2017 in rough seas, the wooden outrigger broke. Captain Sanakoli John and crew had to stop, chop down a tree and craft a new outrigger in order to continue the record-setting journey (video: Thor F. Jensen)

2. Reinstate ancient navigation routes

“Our only way to communicate is the ocean,” says Taumako Island’s Luke O’Grady Vaikawi. “It’s our only highway. There is beauty in that way of moving around the islands. There is now an American border and passport system. We don’t have passports and don’t know how to get them. So our canoe trade with other islands has stopped. We want to reconnect and revive those routes again. We need our ancestral networks for culture and survival. We want to get back to the traditional, sustainable way of living.”

"Women are the custodians of the land and sea in Taumako culture," says islander Delsie Betty Bosi. "The men build most of the canoes; the women feed the workers and children, keeping morale strong, and build the sails of pandanus leaves. They cut the leaves, boil them, cut with coconut fibres into strands and weave. The largest of a five-island archipelago, Taumako is isolated and has no electricity or telephones. It’s five to nine hours in an open boat to reach the other islands for essential trade, cultural exchange and camaraderie" (video: Mimi George/Vaka Taumako Project)

Colonial laws, policies, wars, borders, and replacement of gifting trade and resiliency-rich networks have devastated Pacific Island culture and economies. Here is a recent attempt to reinstate culturally ethical kula gifting, also known as kula trade (video: Gina Knapp)

3. Build a network of ocean caretakers across the world

“We are here to connect with the Indigenous people of Canada and create a relationship; there was a relationship thousands of years before, but it’s taken us a while to get back,” says Fiji’s Setareki Ledua. “Indigenous people still have very important knowledge to share. We want to find our way forward—together. Even though we have come to a different place, with the Indigenous people here, it feels like home. They have the same vision and mission of what they’re trying to do here as us back home. It’s not a coincidence—it’s just a matter of reconnecting.”

Lolobeyong Benito of Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands (photo: Justin Man)

What’s next?

A TePuke voyaging vessel named TeVaka Causey sails for Ndeni Island in June, 2018. Tinakula Volcano juts from the sea to windward (photo: Mimi George/Vaka Taumako Project)

For the Pacific Island knowledge keepers:

Luke O’Grady Vaikawi, Taumako Island: “I learned a lot at IMPAC5 [global ocean protection conference]. I want to go back and tell our people what life is like in this part of the world, how important the ocean is and how we can protect it, and how important the vaka (canoe) is as a means of transportation. We need a world to live in that is sacred and safe, and works for everyone.”

For the world community:

Marianne “Mimi” Kaveia George, Anahola, Hawai'i: "There should be talk about a plan for students to study in ancestral knowledge schools of the Pacific Islands, and for students from those knowledge-holding communities to come to school in Canada. We need another event with representatives from consulates, policy makers, fisheries and young people to plan how First Nations people in BC can enter into active, collaborative relationships and plans with these Oceania-based communities.

For UBC:

Political Science Prof. Yves Tiberghien: “We want to combine everything we’ve learned in a great experiment that pushes boundaries. I hope the experience will touch many of us and give us deep insights that each will take back to our fields. I hope there is a moment of crystallization for a new way of seeing things and expressing things covering an area usually understudied: the area beyond our coasts.”

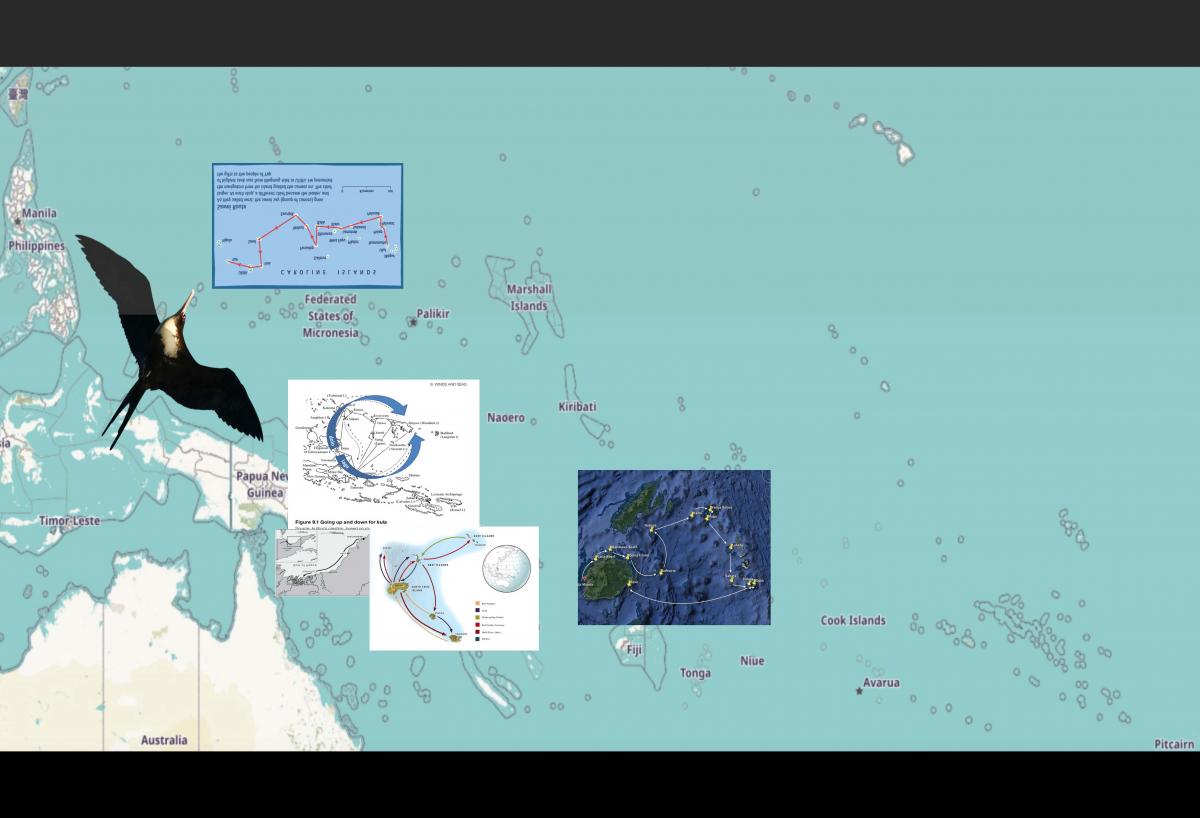

Map

The Pacific Island knowledge keepers who gathered at UBC hail from very different areas of the Western Pacific Ocean and are geographically far apart (map compilation: Mimi George/photos by permission of Hob Osterland (the frigate bird) Susanne Kuehling (the Kula ring), William Davenport, (Santa Cruz network), Drua Sailing Experience (Lau Group routes) and Hasa Hachigchig (Caroline Islands Sawei Route))