One student, Nora Siki in Papua New Guinea, builds a case for breaking down organizational silos and understanding mineral extraction as a business, perhaps the industry’s greatest challenge. Another, James Arhinkorah Appiah, an engineer and aspiring mineral economist in Ghana, addresses “Sustainable Mining: The way forward for a depleting natural resource.” Tuning in today for capstone presentations with the virtual LinkedIn group are students in the Philippines, Romania, Mongolia, England, Germany and South Africa. Some have joined the class at 3 am in their time zone in order to give live presentations, get feedback and sharpen their skills.

“Cultish.” That’s how instructor Benjamin Cox describes the group of hundreds of professionals, ranging from age 20 to 80, who are earning their Executive Microcertificate in Economic Leadership for mining professionals online from UBC’s Bradshaw Research Initiative for Minerals and Mining, or BRIMM. Operating primarily within the Faculties of Applied Science and Science, BRIMM promotes multidisciplinary research teams working with industry to find innovative, sustainable solutions to industry challenges.

Meeting on LinkedIn at all hours: the BRIMM Executive Microcertificate in Economic Leadership class for mining professionals, from top to bottom, left to right: Benjamin Cox, Reza Parvizi, Ben Murphy, Megan Frederick; Janelle Smith, John Korczak, Jasper Escuro, class student; Simon Peter Dagbui; Faustin Kamah, Warilika Sam, Jacob Bilous; class student, Heli S., Adrian Forsyth (photo: Benjamin Cox)

“You’d think we have some kind of magic Kool-Aid,” says Cox, who directs the microcertificate program. “The level of engagement is insane. Why? Because most people who teach genuinely think they know the answers. We discuss problems. The world needs far more discussion of ‘this is the problem’ versus ‘these are the answers.’ We (as educators) need to break the system. Right now, we’re talking to ourselves around topics that are irrelevant to the world.”

Based in Portland, Oregon, Cox delivers pointed critiques that manage to straddle the line between blunt and gentle, with a dash of saucy humour. “It’s too 1980s,” he tells Mark Larsen, a retired Calgary geological consultant with 40 years’ global experience, who is looking to market his services to multinationals. “Pay someone to fix your PowerPoint. You need to take 20 years off and no amount of Botox is going to change that.” Instead, Cox suggests, “Tell this to us as a ‘hero’s journey’ story.”

Another student relays specifics on how exactly to update the graphics and repackage the information to showcase Larsen’s impressive accomplishments. The group concurs.

“Relax, you’ve got this,” Cox assures another student who falters with technical difficulties at the outset, “take your time.”

Candid discussion is a big part of the popular class – pictured from top: Benjamin Cox, BRIMM's Reza Parvizi and Ben Murphy, with students Megan Frederick and Janelle Smith (photo: Benjamin Cox)

Much of the intent here, Cox says, is changing entrenched culture and breaking down the silos typically sealing off geologists from water engineers, NGOs from executives, and so on. With most international curricula, he quips, “instructors don’t have a concept of what the other type of pavement looks like.” Cox’s approach, along with that of mining executive and course co-creator Ben Murphy, is pragmatic and interpersonal – with the aim of meeting students at their level. “If someone doesn’t own a computer,” Cox says, “midtown Manhattan finance just doesn’t apply.”

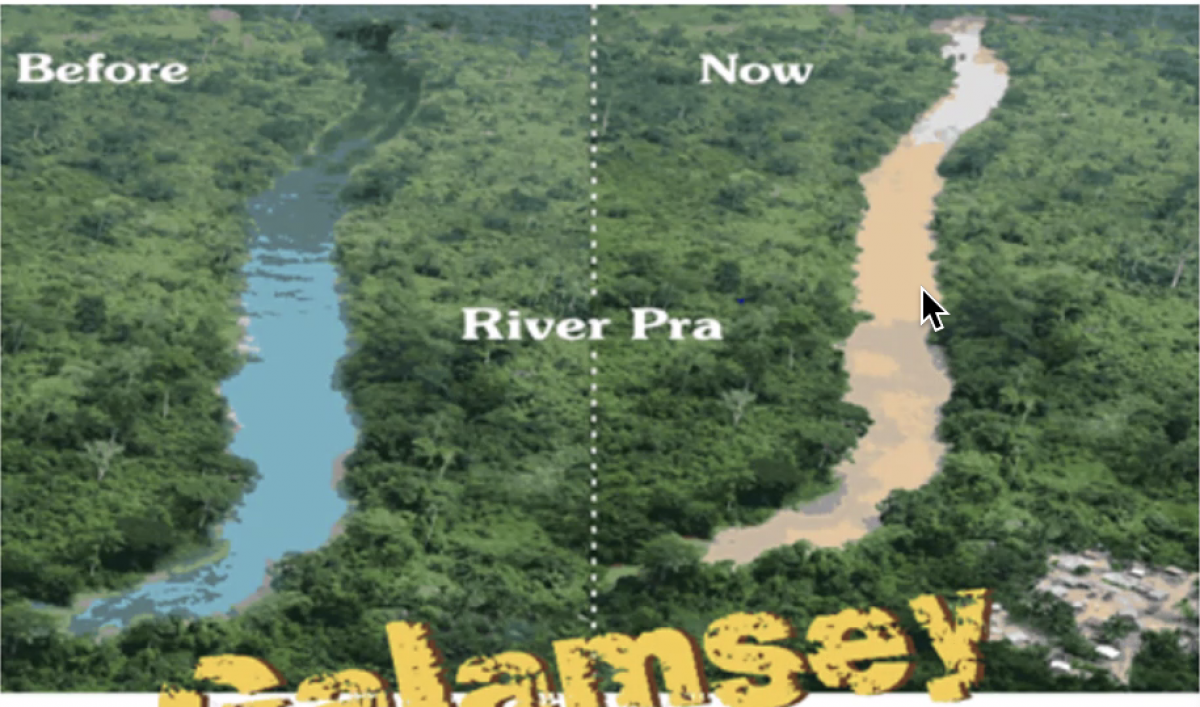

One presenter starts with an arresting image of feet: Encrusted, dirty, infected and oozing, they are the result of black foot disease from Ghana’s 150,000 illegal mining operations carried out by destitute locals without shoes or safety equipment of any kind. “These people are doing this because of the lack of opportunities,” explains Nzubechukwu Ezeonyi, a Nigerian speaking from his current residence in England. “They are poor, unemployed and have no access to the licensing process. So illegal mining is a way to make quick money. This affects people’s health, water bodies, cash crops, food security, the economic situation and national inflation. Think of the good (the government) could do if this were properly managed.”

Black foot disease - a result of widespread illegal mining in Ghana (photo: Nzubechukwu Ezeonyi)

Giving feedback, Cox says: “Stunning, terrifying… Now, to contrast, show us a picture of a clean mining operation. And be sure to show annual compounding inflation on food costs from loss of crop land so that every year adds onto the previous year. These numbers are staggering.”

There’s nothing traditional about Cox, a UBC PhD candidate in mining economics and former DeShaw hedge fund analyst and junior mining executive. And that’s exactly why his course attracts a committed group more akin to disciples than students. When Cox first casually floated the concept for the microcertificate on LinkedIn, 1,400 people signed up; there are now 1,536 members in the LinkedIn group. Since the initial pilot course in June 2019, BRIMM has built a customized platform and learning materials to support the growth of the education program.

There are a few factors at play. First, BRIMM, working with global non-profit organization Women in Mining, started offering bursaries to cover the certification cost, attracting professionals from South Africa and Papua New Guinea. (So far, 37 from 31 countries, all women, have received funding.) Next, based on merit and need, BRIMM offered free spots to candidates from developing economies, where a mining career offers a rare chance for a good salary. Then, the two Bens – or “B^2” as BRIMMers call them – realized many would-be students didn’t have access to a computer. So they quickly adapted the course to run on smart phones and moved the class to LinkedIn. Since its inception, the program has taken nearly 200 students. The first 17 are just now graduating.

A presentation from BRIMM student Nzubechukwu Ezeonyi on impacts of unregulated mining operations (photo: Nzubechukwu Ezeonyi)

“These people are genuinely hungry to learn, and that’s humbling,” says Cox. “They’re getting up at 3 in the morning to learn from you, live. You have an obligation to engage – to show up and not waste their time.”

Trading their valuable work time for education is worth it, the students say.

Ruqshana Hassan likes the diversity of class members, technical insights and expertise she can link to company strategy on commodity movements and investment opportunities, while considering environmental and social impacts. In Johannesburg, South Africa, Hassan is Sibanye Stillwater vice-president and strategic advisor to the CEO, with ambitions for the C-Suite. “Conversations are eye-opening,” Hassan says. “The lecturers are honest, down-to-earth and committed to the end goal of teaching and improving the understanding of mineral economics – very different thinking and doing, with excellent results. ”

Angela Duchesne is a metallurgist with international experience. She says even when discussion veers off on a tangent, it yields insight. “In one class,” she recalls, “Ben expressed his thoughts on switching to dry processes as a way of conserving water. I mentioned an urban example of this: a cement plant in Los Angeles right next to a residential area. Off the top of his head, Benjamin was able to expand on that to explain the economics of the gravel industry and the reasons why that cement plant has to be in urban Los Angeles and not on the outskirts. Then to top it off, he adds that the gravel used in Los Angeles is brought in by Panamax vessels from Vancouver Island. Wow.”

Students delve into practical analysis in UBC's microcertificate for mining professionals class: Benjamin Cox (top), BRIMM's Reza Parvizi, Ben Murphy; students Megan Frederick and Janelle Smith (photo: Benjamin Cox)

Norma Siki, a mine geologist and current stay-at-home mom in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, appreciates the “unbiased,” open approach, current topics and “economic models used live in class to explain, justify and stress-test scenarios” to put things into perspective. Her only criticism, which won’t come as any surprise to Cox, is that she wants more supplemental reading material.

Another con: classes in the middle of the night for many.

“I had to split my sleep to attend the sessions,” says Duchesne, a Canadian living in Hanau, Germany. “It is possible to view the recording afterwards, but I didn’t want to miss the opportunity to participate and ask questions. It’s not often that you get access to this calibre of expertise. Plus, Benjamin and Ben could discuss paint drying and somehow they would make it interesting.”

Find out more about BRIMM’s microcertificate for mining professionals.

Read about BRIMM research programs in mining biotechnology, low-carbon mine energy systems, mine water stewardship and orebody knowledge.