“Local to global to local” is the mantra of UBC Orthopaedics. And one thing Dr. Kishore Mulpuri would like to clear up as the new department head is the common perception – or misperception – of the term “international.”

“People’s perception of ‘international’ is very narrow,” says Dr. Mulpuri, also Pediatric Orthopaedic Surgeon at BC Children’s Hospital. “Mostly, they are thinking ‘first-world’ collaboration. But we need to be a lot more open-minded and push the boundaries. We need to be celebrating our connections and collaborations globally – with the whole world, not just Europe, the UK and New Zealand.”

Dr. Kishore Mulpuri (photo: BC Children’s Hospital)

The Uganda Sustainable Clubfoot Care Project (USCCP), Spinal Cord Injury Collaboration | Nepal (SpiNepal) and Uganda Sustainable Trauma Orthopaedic Program (USTOP) are just some of the initiatives Dr. Mulpuri is championing with his team. The aim of these projects, he says, is sustainable capacity development based on local goals and needs. These initiatives are collaborative efforts driven by partnership and the desire to improve healthcare.

The Uganda Sustainable Clubfoot Care Project (USCCP) is spearheaded by Dr. Shafique Pirani, a clinical professor at Department of Orthopaedics at UBC. This collaborative initiative builds capacity for sustainable care and management of clubfoot using the Ponseti method throughout Uganda. The USCCP is a collective effort between Makerere University, the University of British Columbia, and the Ugandan Ministry of Health.

Spinal Cord Injury Collaboration | Nepal (SpiNepal) – is a program run by Dr. Peter Wing & Dr. Claire Weeks, retired physicians whose specialty is surgical and rehabilitation treatment of spinal cord injuries. The Nepalese Spinal Cord Injury Collaboration or Spine Nepal (SpiNepal) works closely with collaborators at Spinal Injury Rehabilitation Centre (SIRC) – Nepal’s first and only specialized spinal injury unit. SpiNepal participates in training doctors in caring for spinal cord injury.

Uganda Sustainable Trauma Orthopaedic Program (USTOP) – Developed by three orthopaedic surgeons from the UBC Department of Orthopaedic – Drs. Peter O’Brien, Piotr Blachut and Trevor Stone – USTOP is an initiative to improve the education of surgical trainees, nurses and paramedical personnel in the care of individuals with traumatic injury. USTOP is aligned with the mandate of the Ugandan Ministry of Health, and is partnered with Makerere University and Mulago Hospital, a key national referral and training hospital for Uganda and one of only two orthopaedic training centres in East Africa. We spoke with Dr. Mulpuri about equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), and the difference between an approach that’s international versus global.

Dr. Kishore Mulpuri presenting at the 1st annual Hip Hope Network Meeting on May 14, 2022. Dr. Mulpuri is a founder of the Hip Hope Network (photo: BC Children’s Hospital)

What we’re doing right:

What we call “local to global to local.” If we don’t set up good programs, we can’t be attentive to advocating globally or scaling up. It must be something we’ve tried and that we could take to global partners. At the same time, we bring it back here — we ourselves learn a lot from their learnings. We bring them back to local. So it’s local to global, and back to local.

Examples?

Several! One is: We went to Uganda to do a camp-style program. But it needed a public approach, so we partnered with the UBC School of Public Health. We developed a huge program for Uganda, then expanded to many other low- to mid-income countries, then brought it back to us. That one is a great example of closing a whole circle.

Here’s another: With cerebral palsy, a person has a 90 percent chance of gradually dislocating a hip, leading to pain and arthritis. This can be avoided with a screening program, however. We have the only North American program — one of just five in the world. Started in 2015, the Child Health BC Hip Surveillance Program for Children with Cerebral Palsy program has eliminated hip dislocations altogether.

There is now an opportunity (for BC Children’s Hospital/the Hippy Lab) to work hand-in-hand with nine different medical associations in India, representing 120,000 people, to develop care pathways in hip surveillance for pediatric hip conditions. That said, “global” doesn’t mean you need to go physically to India. We’re doing 40+ Zooms a year. When you’re engaging in global efforts, they’re not always at the most convenient time (for us). It must happen at the most convenient times for them, which means 11 pm here. If you’re trying to help someone, you help them at a time convenient for them, not for you!

Dr. Kishore Mulpuri performs surgical work during recent travel to India. Dr. Mulpuri visits India regularly to meet with collaborators and participate in surgical and clinical knowledge exchange (photo: BC Children’s Hospital)

What we’re getting wrong:

It’s not about the one week we travel to engage globally; it’s about what we are doing the other 51 weeks. How are we engaging? I measure efforts by the commitment for 52 weeks, not one. Typically, we fly with the team to there from here, do a program for one week and come back. There is a place for that, yes, but you are not really going to set up that partner for success and make meaningful impact (with that approach).

Overarching goal:

We need more teaching and training for the whole world. We need to stop with the lip service of saying we care about the world – we have to show it. We have fellowships (at UBC) where approximately 200 fellows a year come to help improve our clinical care, like consultants who take part in our research. It’s amazing to have these people, but 90 percent of them come from four countries: the U.S., Australia, New Zealand and the UK. The other 10 percent are from the rest of the world. It’s a deep-rooted problem. We completely ignore centres where the need is the most. It’s important we engage with not just 10 percent (of the world’s population), but the 90 percent who really need us.

Current focus:

Right now, we have 24 unique fellows at UBC who started in orthopaedics from 15 different countries and six continents. It’s diversity that’s globally minded. We have people from Kenya, Uganda, Libya, South Africa, India, and Saudi Arabia. In terms of value, even though some might not be at the level of developed nations, the benefit when they go back to that country and the linkages they build are huge. This is an opportunity that exists today.

What we need now:

The Faculty of Medicine needs to be more thoughtful about recruiting global student collaborators. If we’re thoughtful about giving entry to say, 10 graduate students from low- and middle-income countries, we tangibly change the research and connections to those countries. It requires commitment from staff and the Faculty. From Australia, grad students have the funding. From low-income countries: sorry, they don’t. We need to put in a stool, so to speak, to bring people up to that level.

Dr. Kishore Mulpuri with the Hippy Lab at BC Children’s Hospital. Dr. Mulpuri is the Hippy Lab lead (photo: BC Children’s Hospital)

Biggest misconceptions:

First, we think that we treat (global partners) how they like. In reality, we engage how we want to engage. I asked global surgeons about that in a survey, and most talked about mission trips, weeks spent in low-income countries providing care. On the flipside, we asked people in low-income countries, what is the biggest need? They said in creating education and capacity; not someone coming for a week and to help with surgeries. We don’t include them in the conversation, asking what they need. It’s about them, not us. A dialogue is two people. That’s important to reflect on.

Second, a misconception is that people here are waiting for funding to come. They aren’t realizing the opportunities they have right in front of them. Those who can’t travel because they have children at home can jump on a Zoom call and donate 10 hours of their time to a university in a low-income country. Imagine the hours of teaching that could go to these universities. We have yet to even scratch the surface. We need to ask, what can we do? What can we do from here? What can we do now?

Inspiration:

UBC’s new global engagement strategy, In Service, is so inspiring because it completely resonates with what we do. It talks about “students as global citizens,” and our team is exposed every day and interacting with fellows from low-income countries. We’re talking with researchers on collaborations with Kenya, India and China – to me, that’s what global engagement is. Everybody talks about EDI. But when you go into the true sense of it, very few get what it means — and how it relates to being globally minded. The essence is: service and collaboration as equitable partners.

Piece of advice:

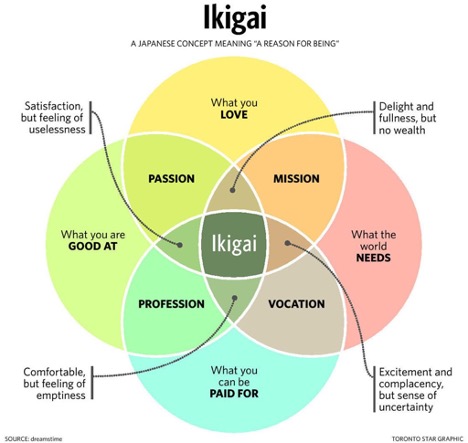

Always ask, what is the ikigai? Ikigai is a Japanese term meaning “reason for being.” It’s the intersection between what you’re good at (I’m an orthopedic surgeon) and what you can get paid for. Then next is what you love. (I love taking care of patients, teaching and training). What the world needs is the last element of ikigai, but it’s often missing. If the intersection is right, it gives me my profession, my passion. But if I’m missing what the world needs, I miss my mission and vocation. The sweet spot is ikigai. True, I’m tired, but I’m pumped. I love what I do. What I tell young students I come across is to really reflect on this. We all get paid well and we are good at what we do. But, are we doing what we love? Are we doing what the world needs? If not the last one, that leads to emptiness, unhappiness, burnout… helping others in general, in the end, helps you.

Diagram of Ikigai (source: Dr. Kishore Mulpuri)

Find out more about the UBC Department of Orthopaedics.

See an overview of UBC Orthopaedics global initiatives.